Assessment fundamentals

Explore information about principles of good assessment, formative assessment, scaffolding, review strategies and retrieval practices.

About assessments

Assessments allow faculty to gather information about learning and determine whether students are successfully achieving the learning goals of the course.

Principles of good assessment and formative assessment work together to form the foundation of successful assessment.

By including scaffolding and review strategies, faculty can support students as they work to demonstrate their learning of the course learning outcomes.

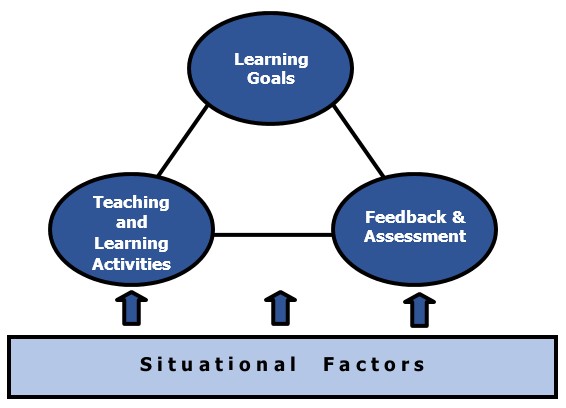

Integrated Course Design (ICD) is a model that places assessment within the larger context of the course and demonstrates its interconnectedness with learning goals and teaching and learning activities.

This graphic model illustrates both the basic components of ICD, as well as their interrelatedness.

Principles of good assessment

The nine principles of good practice for assessing student learning described below were developed through the American Association for Higher Education. They offer a framework for thinking about assessment.

An effective assessment strategy:

- begins with educational values (philosophies of teaching and learning). It measures what’s important, not just what’s easy.

- is multidimensional and measures learning over time. It employs a variety of methods to assess knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, and habits of mind in a particular discipline.

- has clearly and explicitly stated goals and purposes. These goals are shared with the learners in a way that’s meaningful.

- pays as much attention to the experiences that lead to outcomes as to the outcomes themselves. It monitors student progress towards the defined outcomes.

- is ongoing, rather than episodic. It monitors progress with the goal of continuous improvement in teaching and learning.

- improves the entire educational community. It is based on standards that are supported by employers, faculty, librarians, student services, administrative staff, and management.

- connects information to authentic, meaningful and relevant assessment tasks. It involves learners in questions they care about and activities that matter.

- is part of a campus-wide strategy to improve the quality of teaching and learning. Institutional planning, budgeting, decision-making and performance measures are visibly linked to educational improvement.

- considers the responsibility of education to continually improve individuals and society.

Considerations

When designing the assessment strategy for a course, faculty should consider the following:

- How is your philosophy of teaching and learning reflected in your assessment strategy?

- How effectively does your assessment strategy support and measure defined outcomes?

- What aspects of your assessment strategy are linked to essential skills (i.e. employability skills), learning strategies, and/or habits of mind for your discipline?

- How authentic and meaningful are your assessment tasks?

Ideas and strategies

For each principle, below are some ideas and strategies for putting it into practice.

- Include information about your educational philosophy and its link to assessment in your syllabus.

- Provide a rationale for all assessment activities and link them to learning outcomes.

- Have students put assessment criteria into practice (i.e. have students grade some sample assignments; have students evaluate or design test questions based on certain criteria).

- Solicit student feedback on learning and assessment experiences (i.e. stop, start, continue).

- Include a variety of assessment strategies in the course to appeal to various learning styles and intelligences; offer choices if possible.

- Incorporate Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles.

- Focus learners on the need-to-know information and its application.

- Communicate assessment criteria and rationale both verbally and in writing.

- Develop rubrics to communicate the differences between levels of performance.

- Break learning outcomes down into building blocks and slowly build knowledge and skills.

- Assess at various stages/steps of the process, not just at the end.

- Structure classroom activities similarly to assessment activities so students can practise.

- Use a lesson planning model to guide instruction.

- Engage students in discussion about their learning and the learning process.

- Include formative assessments as part of your assessment strategy (i.e. group quiz, games, one-minute paper, 10-question review, muddiest moments, etc.).

- Assess milestones in the process instead of just the final product.

- Engage students in self-assessment; give them tools or strategies they can use to monitor learning.

- Develop a clear understanding of industry expectations and structure assessment accordingly.

- Identify essential skills within learning outcomes and assess them with discipline specific outcomes.

- Access resources throughout the college to facilitate teaching and learning of essential skills.

- Connect your subject area to things students care about (i.e. ask them what they hope to get out of the course, or what life questions and/or challenges learning in your course might help them with).

- Structure assessment tasks so students must make connections between course content—theories, concepts, and models—and the world.

- Develop assessment activities that integrate several learning outcomes (i.e. projects, portfolios).

- Design assessment tasks that reflect current problems and challenges in industry.

- Use external evaluators to assess some aspect of learning and/or performance (i.e. project, portfolio, performance, product).

- Participate in program renewal processes and in program curriculum discussions.

- Get involved in campus-wide initiatives that strive to improve teaching and learning.

- Include moral and ethical dilemmas of the industry in teaching and assessment.

- Reflect on the changes—cognitive, psychomotor, affective—that have helped you as the faculty be successful in the industry; try to build these into assessments.

- Strive to continuously improve student learning (i.e. re-evaluating teaching and assessment strategies).

- Structure assessment tasks that take students out into the community or require them to utilize community resources (i.e. interviews, field studies, directory, profiles).

References:

Astin, Alexander & Banta, Trudy & Cross, K & El-Khawas, Elaine & Ewell, Peter & Hutchings, Pat & Marchese, Theodore & Mcclenney, Kay & Mentkowski, Marcia & Miller, Margaret & Moran, E & Wright, Barbara. (2022). American Association for Higher Education (AAHE) Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning 9 Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning.

Formative assessment

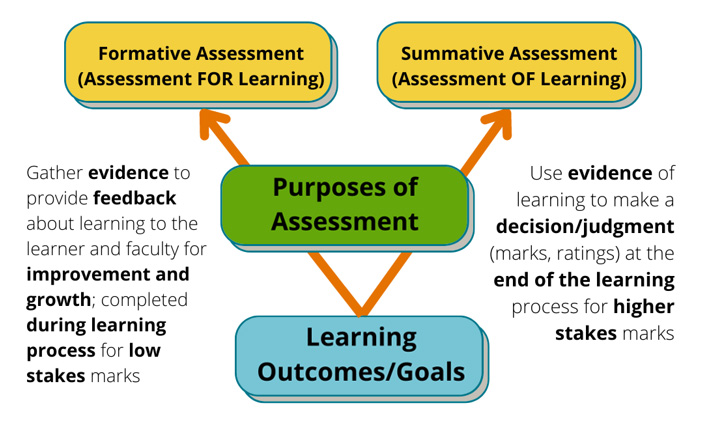

Formative assessment provides feedback to the faculty and the student during the learning process (as opposed to summative assessment, which evaluates learning at an end point). Formative assessment is assessment for learning, and should be an integral part of the teaching and learning process.

Research shows that an increase in formative assessments can produce significant learning gains if it is properly planned, implemented and evaluated.

- Formative assessment should be linked to identified and communicated learning objectives and assessment criteria.

- Formative assessment should be used as a feedback mechanism to identify learning gaps for both the faculty and the students.

- Faculty must use the results to make the necessary adjustments to instruction.

- Students must use the results to identify the knowledge and/or skill gaps they need to address to improve summative evaluation results.

Considerations

When considering formative assessment within a course, faculty should consider the following:

- What are the learning objectives that you are trying to assess?

- What type of formative assessment will provide meaningful, efficient feedback to both the faculty and the students related to the objectives?

- How can the assessment activity be made time-efficient (i.e. minimal or no marking, doesn’t take up too much class time)?

Ideas and strategies

- The faculty will get feedback on their explanation of the concept.

- Students will clarify their thinking as they verbally express the concept.

- Other students can provide feedback on the explanation (i.e. confusing, incomplete, too much detail, adequate, excellent).

Oral multiple choice questions where students vote on the correct answer.

Online quizzes that students complete multiple times, until they feel they have an adequate grasp of the material.

Students answer/solve quiz questions/problems as a team, competing with other teams (i.e. use a popular game show format).

Consider the following questions:

- What were the key points of this topic?

- What aspects of the topic are still unclear?

- What is a question you still have after today’s class?

Responses can be written on an index card, posted online, consolidated in groups and posted around the room for discussion, etc.

Self-assessment tools such as rubrics, checklists and rating charts, where students can assess their own performance.

Peer-assessment activities where students provide feedback on each other’s performance using a clear and structured outline of assessment criteria (i.e. rubric, checklist, rating chart).

- In quadrant A, students identify one thing the faculty is doing that is helping them learn and should stay the same.

- In quadrant B, students identify one thing the faculty is doing that is not working for them, and that they would like to see changed.

- In quadrant C, students identify one thing they are doing themselves that is helping them learn and that they would recommend to other students.

- In quadrant D, students write down one thing they might do themselves to improve their learning in this subject.

The faculty poses a problem or series of questions to students based on the instruction.

Students formulate an individual response, compare it to a partner’s response, and then compare it against a model of excellence.

Students then share challenges, barriers or questions related to achieving the ideal response.

There are many free and easy-to-use digital solutions for gathering formative assessment data that streamline the collection of student responses and assessments, while providing faculty with the ability to easily collect and organize their student data.

Many digital assessment tools can also be used to quickly gather students responses and gain better insight as to which pieces of content require more or less attention. Learn more about tools for assessment.

Adapted from: National Research Council. 2001. Knowing What Students Know: The Science and Design of Educational Assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Scaffolding

What happens to our brains when we learn something new? The brain changes structure and function in response to experience. It’s all about connections. This ongoing dynamic process occurs as the brain rewires itself in response to changing conditions—plasticity. As the brain pathways are used and strengthened, learning is also strengthened.

Based on research, an important aspect of instruction is building structures or networks that support learning in a particular discipline. Scaffolding resources are designed to provide support for students to develop their higher-order thinking skills and transition into being about to handle the subject matter more independently.

Scaffolding resources provide structure to help learners with:

- organizing and processing information

- working through a thinking and/or problem-solving process

- following procedures

- completing tasks

- developing skills

Scaffolding develops confidence with thinking and process structures. Those structures need to provide a solid framework without being a straight jacket for creativity. This is the balancing act; scaffolding must support, but not limit, the construction process.

Considerations

When considering scaffolding for an assessment, faculty should consider the following:

- As an expert in your discipline, what processes and frameworks do you use for organizing, thinking about, and communicating information and ideas?

- How can you make those processes and frameworks more explicit for your learners?

- In your course or discipline, what aspects of learning (i.e. knowledge, skills) pose consistent difficulty for students?

- What resources could provide support and structure in those areas?

Ideas and strategies

To scaffold a major assessment, consider these steps:

- Write a brief description of the assessment, including skills that will be evaluated.

- List what skills students will already need to have to be successful.

- Determine if the students already have the skills they need to be successful. If not, these should be scaffolded into your current course to help prepare the learner to be successful.

- Look at the scope of the course. Design mini assessments or experiences to offer learners time to learn and practise these needed skills.

- Create a map or outline detailing how each major assessment is scaffolded.

- Be transparent with students about the scaffolding steps and course design that support their learning.

- Share the scaffolding rationale with others teaching the course.

Types of scaffolding

Experts use frameworks in their disciplines intuitively (i.e. scientific method, problem solving, design processes, planning frameworks).

Making frameworks explicit allows learners to spend more time working with the content.

Charts and other visual organizers (i.e. timelines, Venn diagrams, trees, flow charts, outlines, storyboards, tables, graphs, diagrams) provide clear structures for extracting, organizing and processing information.

Breaking complex tasks into steps provides the structure many students need to get started on and complete a learning task successfully.

Such guides encourage faculty to articulate how they, as experts, work through the task.

Guiding questions help learners focus their attention and act as a filter for large amounts of information.

Faculty don’t generally have time to teach students all the skills they need to effectively complete assignments. However, we can provide them with supporting informational resources for reference.

Self- or peer assessments are generally only effective when students have clear structures and guidelines that help focus their attention and give them the language they need to give constructive feedback.

References:

Anne Trafton | MIT News Office. (n.d.). Neuroscientists reveal how the brain can enhance connections. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved June 30, 2022

Caruana, V. (2017, September 8). Scaffolding student learning: Tips for getting started. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. Retrieved June 30, 2022

Scaffolding learning in the online classroom. Center for Teaching and Learning | Wiley Education Services. (2020, September 1). Retrieved June 30, 2022

Review strategies and retrieval practices

When learning new content, review strategies are so important because they promote retrieval practice that is drawing information from memory and then storing it again with even stronger neural connections. In many studies, intentional retrieval practice has a significant impact on learning (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel. (2014)). For more information on retrieval practice in higher education, visit the Retrieval Practice website.

Review strategies help to strengthen memory related to course material, reduce testing anxiety, and increase student confidence in their learning (Lang, J. (2016).

For ideas and tips, visit Retrieval Practice: The Most Powerful Learning Strategy You’re Not Using | Cult of Pedagogy

Ideas and strategies

Some key ideas on retrieval practice are listed below:

- It is not the same thing as assessment; low or no impact on student grades.

- Space practice; small chunks are best.

- Include feedback to support students on the learning path.

- Match the practice to the assessment. If higher-order thinking is needed on the assessment, include this in the practice.

Sure-fire strategies from experienced faculty

In the Centre for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at Georgian, we realize that most experienced faculty have many successful review strategies already built into their courses. However, if you are relatively new to teaching, here is a list of sure-fire strategies gathered from faculty, as well as some that we have used successfully ourselves. Thank you to faculty who have shared their favorite strategies!

Students work at completing a quiz collaboratively. They submit one copy of the quiz as a group. This requires students to discuss answers so that everyone agrees.

Alternatively, students could complete the quiz individually first, hand that one in, and then work on the collaborative one.

Have students work in pairs to quiz each other, changing roles between questioner and responder after a predetermined block of questions.

In class, put the students into groups and assign a chapter to each group. Have each group review the chapter outcomes and make the outcomes into questions. Then, have each group work on point-form answers to the questions.

To share the content with the class, have students type up their work and post it on Blackboard, so that those who want to review have access.

Have students work to create a list of things they believe will be on the test and why.

Students then share what they have on their lists with the class, and the faculty member can use some way of giving feedback on the importance and whether they have a good understanding or not.

Have students work in pairs or teams to create questions and answers to challenge classmates.

As faculty, you can commit to using some of the questions on the test. The questions rotate amongst the groups and then are marked by the group that created them. This could be completed in person or via a shared online document.

Provide each student with a diagram of a process that they need to know for the test.

In a pair, each student will have a different diagram. Student A teaches their diagram to student B by writing in the labels and explaining the process. Student B can provide feedback along the way.

As a large group, you can clarify anything that was unclear. Then, student B teaches their diagram to student A using the same process.

Working with students to visually map out a process and having them practise this mapping can re-inforce the neural networks related to that process.

For examples, visit 19 Types of Graphic Organizers for Effective Teaching and Learning.

Provide review questions focused on various units, topics, or concepts.

Students get a certain amount of time at each station and move around the room, adding, reading and revising existing content.

Take photos of the responses and share them. Stations could include tips for learning and remembering.

Review questions are written on the front of an index card and answers are written on the back.

Students ask two people their question and then they switch cards with someone to get a new question.

Terms or concepts are written on a bingo card.

Students have to explain three different terms to three different students, and have three terms explained to them to get a bingo.

Have students write down five or more things they can remember related to a topic.

Have different parts of the class focus on different topics.

Students first write what they can remember individually, and then they work in pairs and compare their lists.

Have each part of the class present back their list on the topic they worked on. As faculty, you can then fill in the blanks on anything important that was missed.

Placement activities create a space for both individual and collective voices related to topics. They can be used to explore what students already know about a topic and to build shared knowledge.

Individuals take a few minutes to write their responses and ideas related to the topic in their quadrant. Then, each person takes turns sharing something that they wrote down, and if two or more people agree, it goes in the centre circle. Finally, faculty can have various groups share one or more things from their centre circle. Groups can be asked to prioritize thoughts before sharing in the large group.

Targeted cases can be a great way to help students review learning at all levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. It is a great way for students and faculty to see how well students are able to apply information and use it to analyze a situation.

When using cases for review, it’s important to structure the activity so students focus their efforts on the appropriate knowledge and thinking.

This online crossword puzzle maker allows you to easily enter text and create a crossword that can be produce either online, as a PDF, or as a Word document.

To get started, check out Free, Online Crossword Puzzle Maker – Crossword Labs.

Simple questions at the beginning or end of class can engage students in retrieval practice.

Exit tickets or “Ticket Out the Door” can be a great way to have more students feel accountable for writing something since they have to hand it to you on the way out the door.

A quick read through the responses can give you, as the teacher, great insight into students’ grasp of a topic. This can also be done using Socrative, which allows short answer responses and tracking.

At the beginning of the class, try “From memory, try to list at least five things we talked about in the last class in relation to Topic X” or “Here is a list of terms from last class. In pairs, come up with one example of each and be ready to explain why it is a good example.”

At the end of class, try “Describe in your own words how _________ process works.” or “Without looking at your notes, explain why __________ is important in this subject.”

Strategies based on educational technologies

There are many digital tools that can be used to support the review and retrieval of information and gain deeper insight into student learning. The learning technologies webpage lists many free tools that are commonly used at Georgian.

References:

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L. III, & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: everyday lessons from the science of learning (First edition.). Jossey-Bass.

Retrieval practice: The most powerful learning strategy you’re not using. Cult of Pedagogy. (2020, June 13). Retrieved June 30, 2022